I recently worked with colleagues to offer similar workshops at two conferences – SCoTENS 2017 in Dundalk (with Pamela Cowan from Queens University Belfast and Elizabeth Oldham from Trinity College Dublin), Ireland and ATEE 2017 in Dubrovnik, Croatia (with Nina Bresnihan, Glenn Strong and Elizabeth Oldham, all from Trinity College Dublin).

The workshops introduced our ideas about using a version of paired programming to give confidence to novices in programming. We had developed these ideas, together with colleagues Mags Amond and Lisa Hegarty, also from Trinity College Dublin, through the CTwins project funded by Google’s CS4HS – Computer Science for High School.

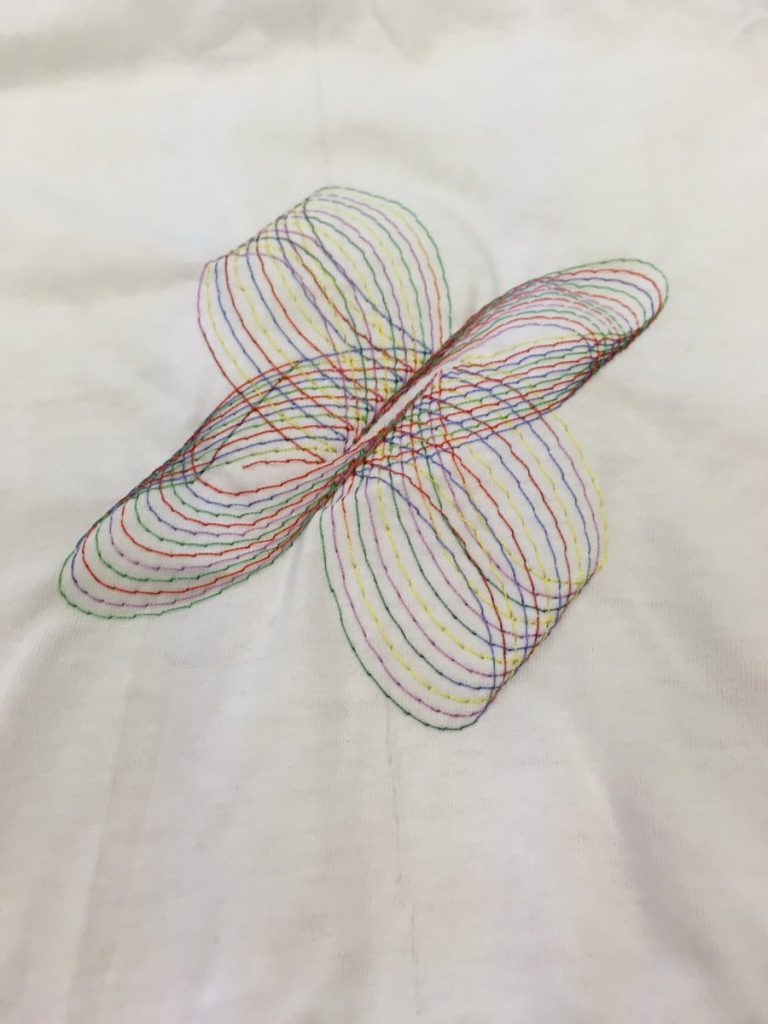

The workshop slides for ATEE 2017 also included ‘Art’ in the title, since it was my notion that developing an art project would be personally fulfilling.

You can see how I have been a little pre-occupied with the relationship between art, craft and programming through my recent blogs:

In a happy co-incidence, I today found myself in a useful conversation about the design of the programming tool, Scratch, that we used in the project and the workshop. In the conversation, we rightly focussed on the design of Scratch, which has become so wildly popular that a heavy weight of responsibility lies on the development team to get it right. I tried to explain why Scratch is important in this blog post:

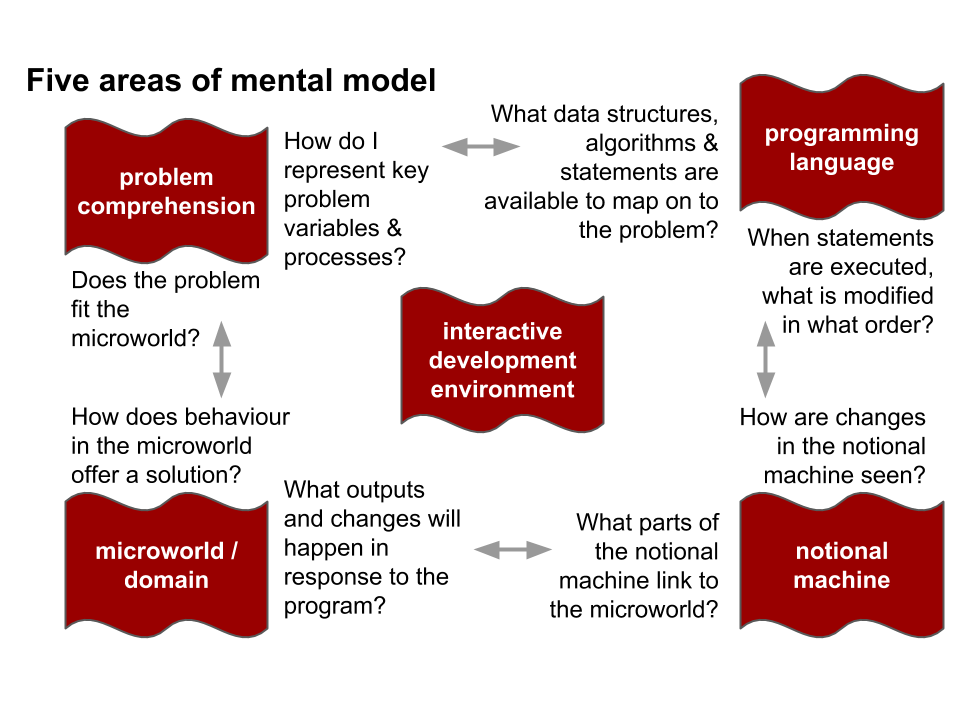

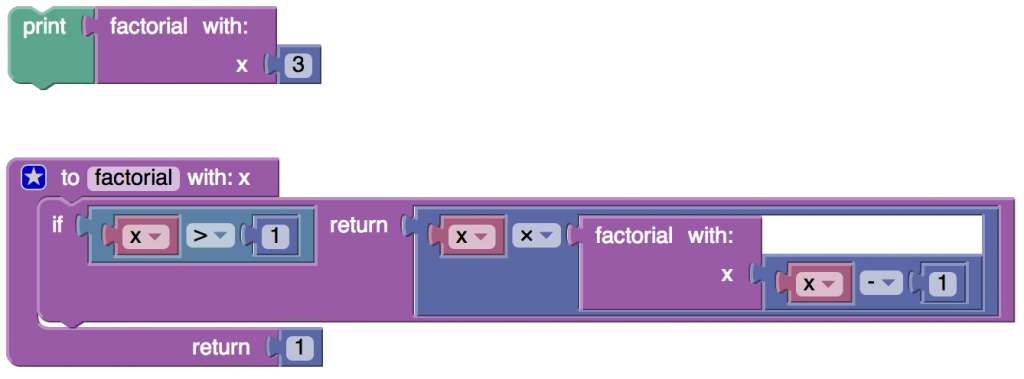

Nevertheless, I feel that as well as considering the tool design, we must also shift attention to the activity and mental models that I believe learners symbiotically develop alongside their use of the Scratch tool. The Logo programming language developed in 1967 and its turtle geometry microworld is one of the most potent developments to recognise such activity and mental modelling – although I believe not the earliest (I believe sentence generation using lists preceded it?).

A microworld is a slippery concept, but Richard Noss and Celia Hoyles neatly sum up its importance in their book ‘Windows on Mathematical Meanings: Learning Cultures and Computers‘:

“In a microworld, the central technical actors are computational objects. The choice of such objects and the ways in which relationships between them are represented within the medium, are critical. Each object is a conceptual building block instantiated on the screen, which students may construct and reconstruct […]. To be effective, they must evoke something worthwhile in the learner, some rationale for wanting to explore with them, play with them, learn with them. they should evoke intuitions, current understandings and personal images – even preferences and pleasures. The primary difficulty facing learners in engaging directly with static formal systems concerns the gap between interaction within such systems and their existing experience: it is simply too great. That is why computational objects are an important intermediary in microworlds, precisely because the interaction with them stands a chance of connecting with existing knowledge and simultaneously points beyond it.”

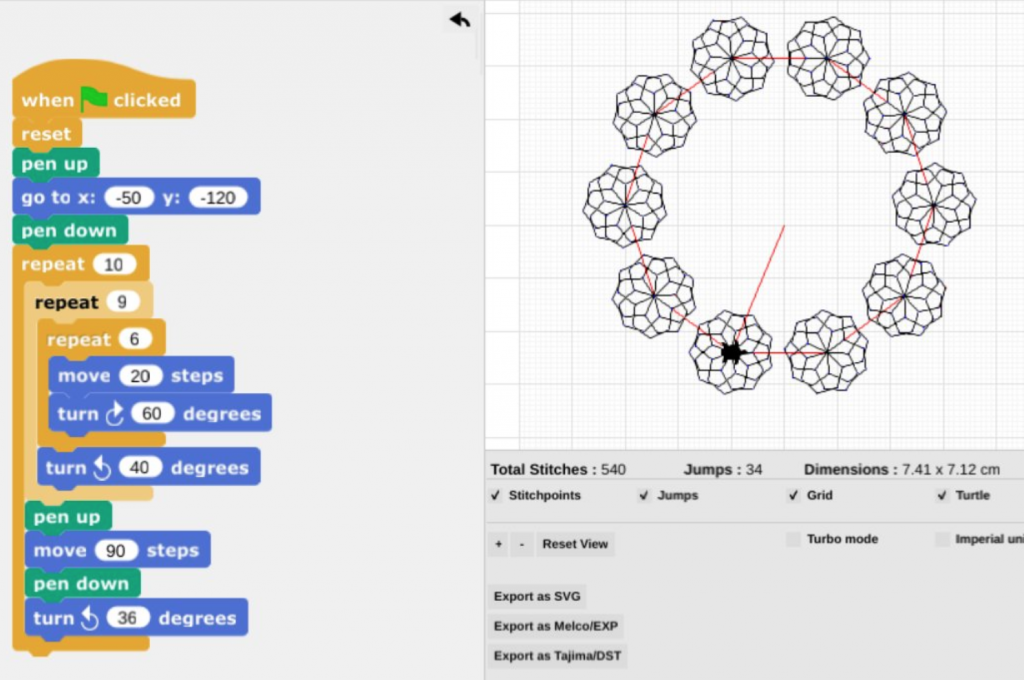

In the turtle geometry microworld, the computational object is a robot turtle on a stage, equipped with a pen to trace out lines as it moves according to program steps.

Scratch starts with a different microworld sporting a cat rather than a turtle and is a particular kind of computer game with interacting sprites. It leaves in the jigsaw blocks for a turtle geometry microworld but they are somewhat spoiled by the sideways view of a stage rather than the top down view of the space that the turtle inhabits.

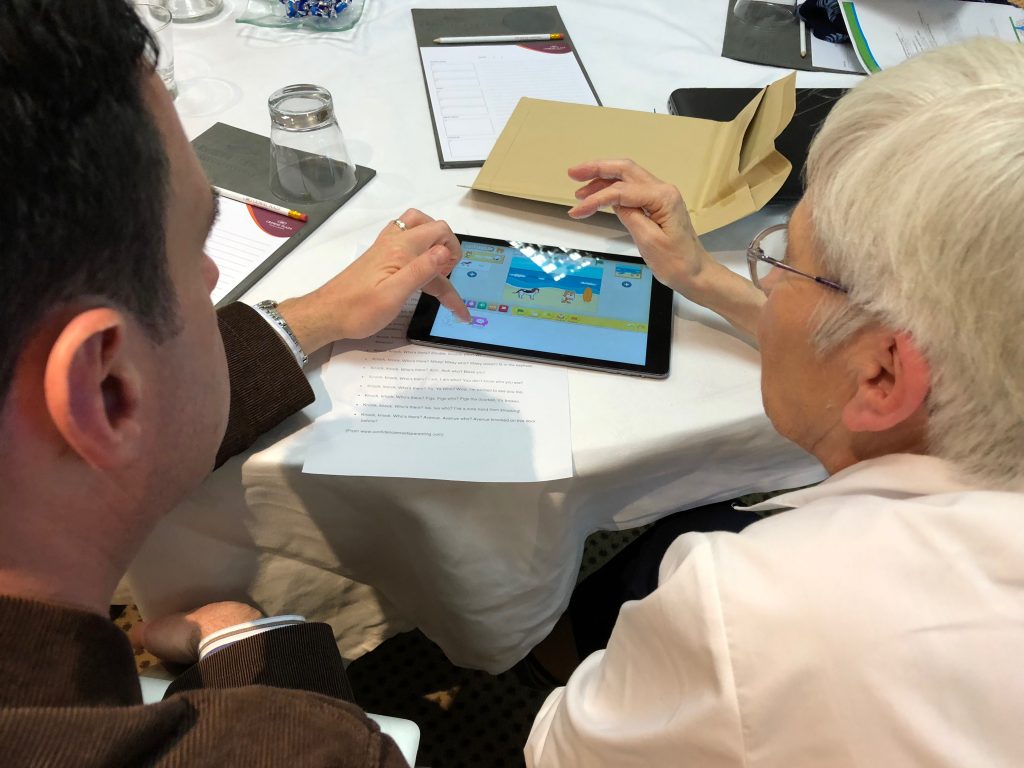

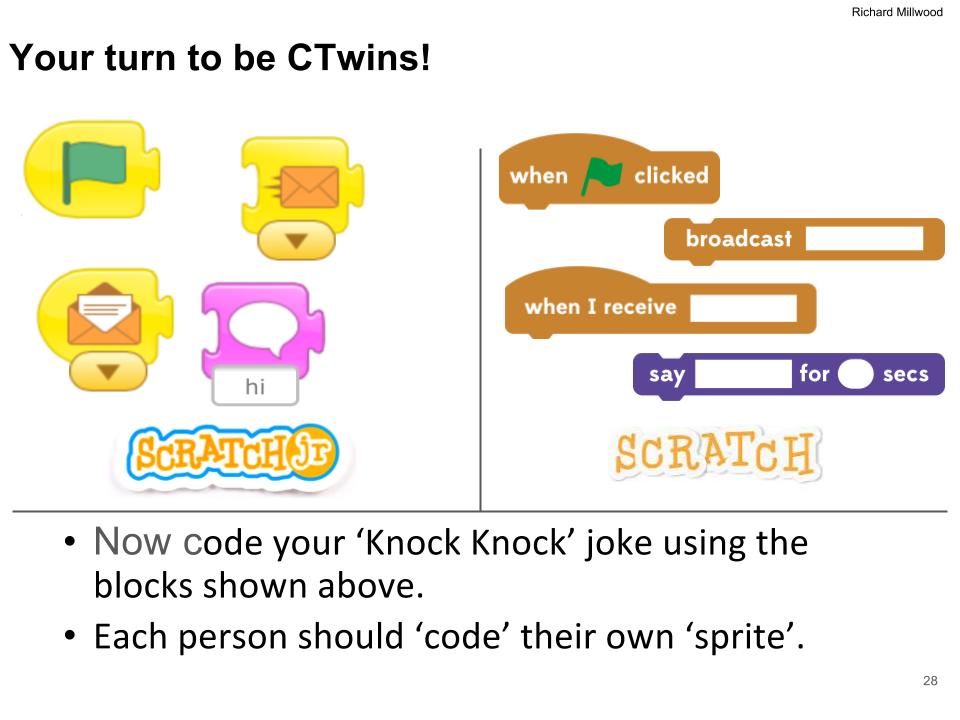

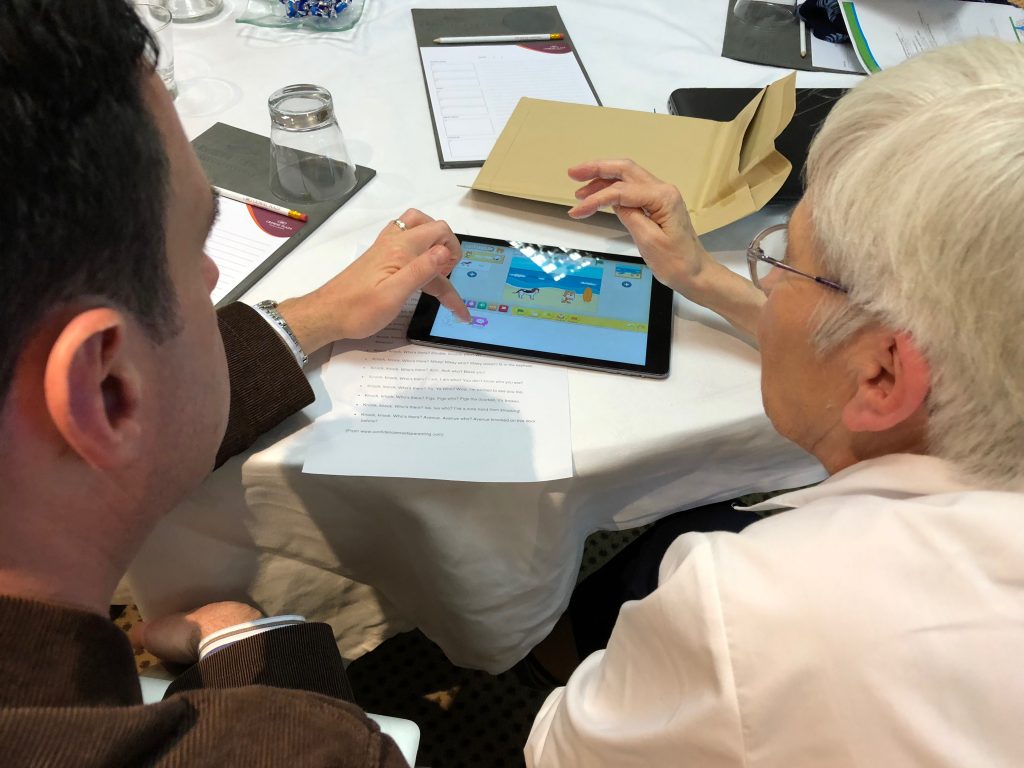

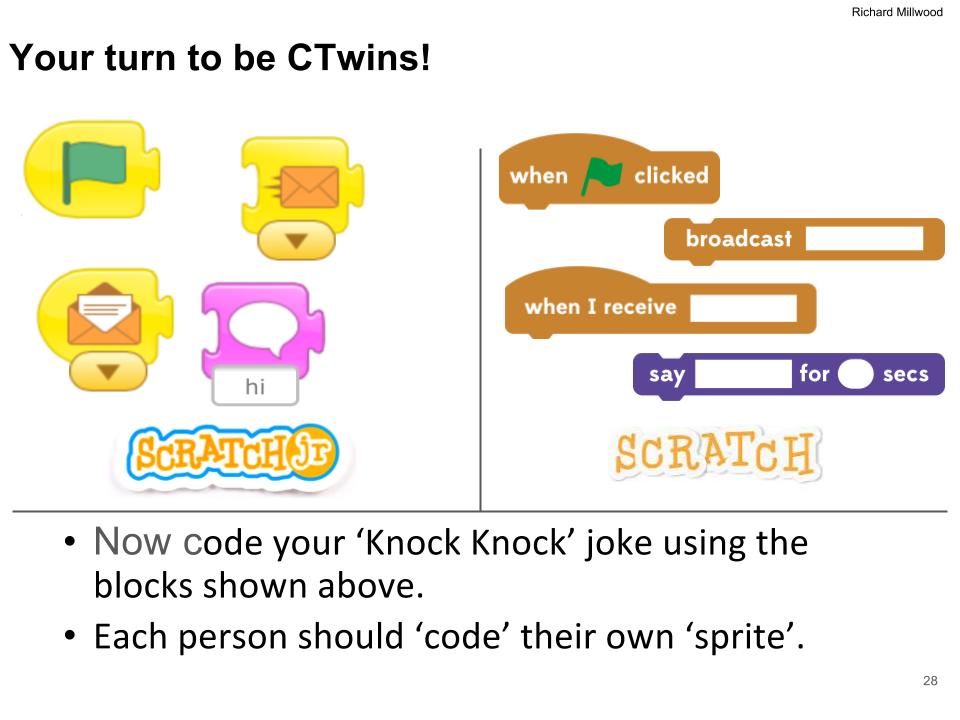

In the conference workshops we asked completely novice learners (adults using Scratch and ScratchJr) to program knock-knock jokes, with two sprites and message passing to synchronise the joke-telling activity.

Firstly, together with colleagues, we performed this joke (thanks to Pamela Cowan for such an excellent idea, performance and preparation):

Ghost: Knock knock!

Cat: Who’s there?

Ghost: Boo!

Cat: Boo who?

Ghost: No need to cry!

Secondly, we asked the adults to humanly perform their own jokes working in pairs, so that one adult would be the first actor in the joke and the other the second. I was building on the concept of ‘body syntonic’ which is so powerful in the turtle geometry microworld, but in this case, it is the act of interactive joke telling that forms the mental model of the problem, to be then expressed formally in programming and debugged.

In the Scratch turtle geometry microworld, the pen jigsaw blocks are the foundations of formally expressing the acts of an imagined turtle with its pen. Children (and adults) can ‘be’ the turtle and act out the actions either bodily or in their heads, exercising their mental model of the turtle, which may then help them debug their formal expressions in code (jigsaw blocks).

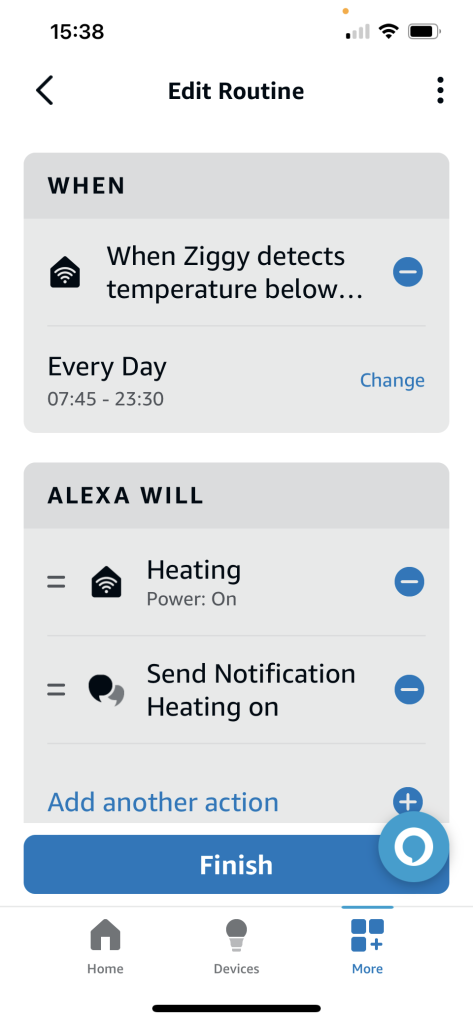

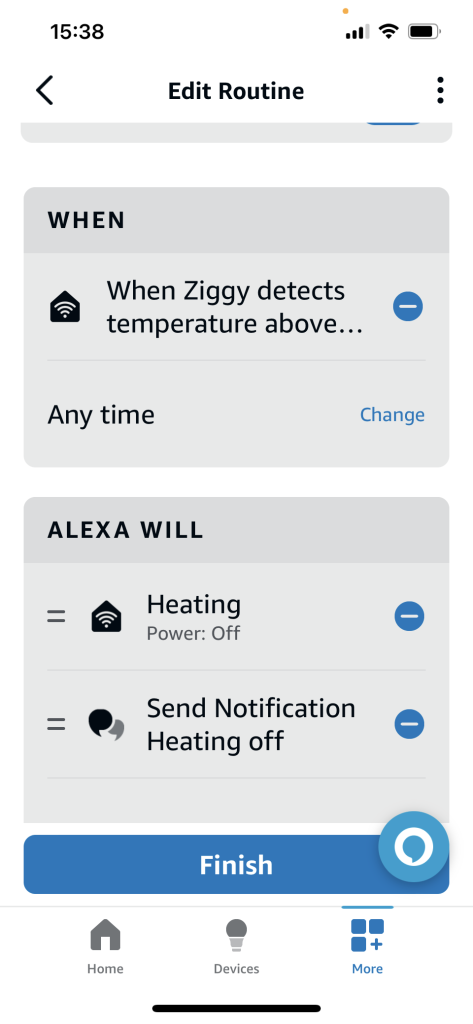

In the case of our knock-knock microworld, we presented on the projector screen a subset of jigsaw blocks to start with:

In one instance of the workshop, to my delight, one learner added other blocks, using repetition to tell a more complex joke.

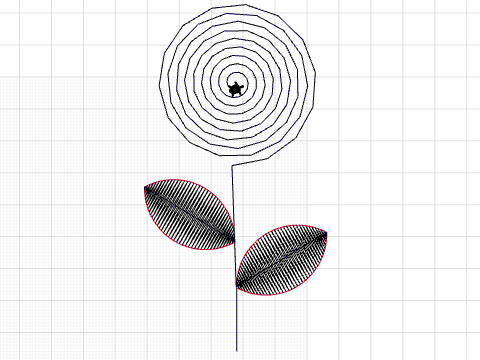

So perhaps the set of immediately available jigsaw blocks should reflect the microworld the learner’s imagination and mental models are anticipated to inhabit? I would go further and propose microworld-appropriate stages (and stage views, as we have in Turtlestitch and Beetleblocks), sprites and costumes. In Turtlestitch I would propose a spider sprite/costume and indeed rename it Spiderart or some-such. Perhaps there should be a choice of microworld, “I’m doing turtle geometry today” which leads one to the set of jigsaw blocks most appropriate to that microworld? I emphatically do not mean that this means restricting access to the wider set of jigsaw blocks, simply that it provides the best recommendations from the menu for the kind of restaurant you want / are ready to eat in.

To extend an already overworked metaphor, after the learner has been eating at diverse restaurants, each founded in the same underlying elements of heat, ingredients and combination, perhaps they would begin to strengthen their knowledge of the invariates which inform the mental models that underly their understanding of notional machine and programming language?

![@AttyMassNS "At the recent [CESI] Conference, we mentioned our plans to explore decomposition and patterns/generalisations through Damhsa/Irish dancing. Integrates with/comhthathú le Seachtain na Gaeilge" March 2018](http://blog.richardmillwood.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/AttyMass-NS-tweet-about-Computational-Thinking-and-Irish-Dancing.jpg)